The Importance of Metaphor

We should never underestimate the importance of metaphor in

ordinary, everyday communication. We use metaphors when we find it

difficult to describe a a 'thing' or an 'experience'. So, we borrow

a word or a phrase, which appears similar to the 'thing' or

'experience', we are trying to describe.

Everyday language is

peppered

with metaphors. We

try to land

contracts at work or read about the

police netting some criminals. Metaphor comes

easily. Indeed, our eyes light up,

when metaphors

ring true. When we are feeling

blue

or our plans are pretty hazy , the last thing we

want is someone taking a dim

view of our colourful

use of metaphor.

Medical language too is

bursting

with metaphors.

People are in tip top condition, then they

fall ill,

sink into a coma, or - in mental

health - experience breakdowns. Medicine opted,

long ago, to adopt mechanics as the overarching metaphor for the

human body. So, the heart is a pump, and the brain

is a computer

- and in Freud's day the mind was a

hydraulic system.

In the psychiatric or mental health field

some people are described as playing mind games and

others risk being brainwashed. Even neuroscience is

replete with metaphors. Neurons are said to be

firing

as information passes along various neuronal

pathways; electrical impulses cross over at various

synaptic junctions, as people experience a

brain wave or participate in a

brainstorming

exercise. All these metaphors depend on the

hardware of the brain; which help the

software

of the mind to do its work. Of course there are no actual pathways

or junctions; hardware or software. We simply could not discuss the

brain without comparing its activities to other things we can see

at work in the world outside.

The Tidal Metaphor

In the

Tidal Model we use metaphors only to

describe the theory of how we function as persons. In Tidal

practice we use only the metaphors that people themselves use

to describe their own experience.

It is not easy to describe,

in simple language, what it means to be a person. Usually, we have

to invoke metaphors - saying it is 'as if' we are like this

or like that. In the Tidal Model we compare life to

a voyage.

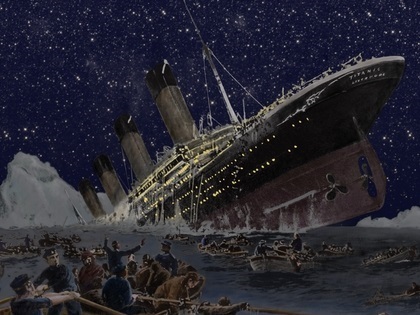

"Life is a voyage, undertaken on an ocean of

experience. All human development - including the experience of

health and illness - involves discoveries made on that oceanic

journey.

The body represents the ship of life and the person is

the captain.

At critical points on the voyage, people may experience

storms, where they may fear becoming all washed up. The ship of life

may begin to take in water, and the person may face the prospect of

drowning or becoming emotionally or psychically shipwrecked. All

these are potent metaphors for the experience of mental or physical

distress and difficulty.

At other times the person may be

boarded by pirates and robbed of aspects of self-hood - the potent

metaphors of the experience of rape, trauma or abuse.

People

who have experienced such human storms need to be guided to a safe

haven, to undertake the necessary repairs that preface their

recovery from the traumas of their voyage. Once the ship of life is

made intact again, and the person has regained their sea legs, the

ship may set sail again, aiming to chart the return to the life

course".

Of course, there is no actual 'voyage' but it is

'as if' we are on just such a voyage.

Psychiatry, madness and mental illness

Like most other life experiences, emotional distress is

always represented in metaphors, ranging from being

'heartbroken' to being 'out of our minds'.

Regrettably, psychiatry and psychology often takes apart the

person's metaphors, transforming the richness of this 'heartfelt'

story into professional jargon.

We have often felt that we

were 'at the end of our tether'. How long, exactly,

that 'tether' might be, we could not say. However,

it expresses, perfectly, our sense of of some reassuring link to

something strong and stable - like a rock or some firm ground. What

that 'tether' might be made of, we could not begin to say, but the

metaphor 'holds'. It 'connects' us (metaphorically)

to something of 'substance' in our lives

Writers

and poets with experience of emotional distress, have given us a

rich catalogue of metaphors to represent such common human problems.

Here we offer two important examples.

Sally Clay ( See

Sally Clay.net)

has written many

powerful essays and poems, all of which represent the 'unsayable'

nature of the 'problems in living' she has experienced. We were

honoured that Sally agreed to write a foreword to our book - "The

Tidal Model: A guide for mental health professionals". (See

Publications)

Sally has had experience of problems in living for over four

decades. She recognises that although some people do appear to

recover, for her recovery is a process, not a place. What she has

been 'doing' to heal the various human hurts that she has

experienced, and that were inflicted upon her, is possibly even more

complex and challenging than entertaining the notion of recovery.

One of Sally's powerful accounts of her struggle with madness

can be found in the book "From

the Ashes of experience: Reflections on madness, recovery and growth".

In her chapter, entitled, 'Madness and Reality', Sally

examined her experience of being put in hospital, repeatedly,

'psychosis', and described how she came to understand what had

happened to her and what it meant.

"Jacob named the

place of his struggle Peniel, which means 'face of God'. I too have

seen God face to face, and I want to remember my Peniel. I really do

not want to be called recovered. from the experience of madness I

received a wound that changed my life. It enabled me to help others

and to know myself. I am proud to have struggled with God and with

the mental health system. I have not recovered. I have overcome"

.

Janet Frame was one of

New Zealand's greatest writers whosew work was introduced to a wider

audience by Jane Campion's film -

An Angel at My Table

- which was based on Janet Frame's autobiography.

Janet

Frame's writing is informed by many distressing life experiences,

including her own descent into what, at the time, was seen as

madness. This resulted in almost a decade spent in various mental

hospitals. She experienced the death of a brother at birth, another

brother disabled by epilepsy, and two sisters who died of heart

failure while swimming, an uncle who cut his throat and a cousin who

shot his lover, his lover's parents and then himself.

Janet

Frame described feeling propelled into a territory that resembled "where

the dying spend their time before death". She added that those

who return alive from such a place bring back a point of view "equal

in its rapture and chilling exposure to the neighbourhood of the

gods and the goddesses". Her book,

Faces in the Water, is a fictionalised account of ten years

spent in a New Zealand psychiatric hospital. Clearly, the book drew

on Janet Frame's own experience:

"I was put in hospital because a great gap opened in the

ice floe between myself and the other people whom I watched, with

their world, drifting away through a violet-coloured sea where

hammer-head sharks in tropical ease swam side by side with the seals

and the polar bears. I was alone on the ice. A blizzard came and I

grew numb and wanted to lie down and sleep and I would have done so

had the strangers arrived with scissors and cloth bags filled with

lice and red-labelled bottles of poison, and other dangers...And the

strangers, without speaking, put up circular calico tents and camped

with me, surrounding me with their merchandise of peril".

The metaphors used by Janet Frame suggest the essence of the

Tidal Model: the journey in and out of 'madness' is

a fraught one, where things rarely are (exactly) what they seem. As

a result, the journey can be all the more perilous for that fact.

The professional helper - whether therapist, nurse, doctor or

social support - can learn much about the nature and meaning of

human distress and difficulty from the person who owns the story of

that distress. First, however, we must acknowledge the importance of

the metaphors. Without an appreciation of the metaphorical nature of

reality, there can be no story, and perhaps no real chance of

recovery.

The Metaphor of Change

The Tidal Model acknowledges that the experience of health and illness is fluid, rather than stable. Most people take their 'health' for granted. Only when they feel different do they realise that 'health' may not be present - and so they feel 'ill'. Indeed, all medical diagnoses of 'illness' or 'disorder' involve change.

The Tidal Model assumes that the only constant is the personal experience of change. This is hardly a new perspective on human affairs. Two and a half thousand years ago Euripides observed: "All is change; all yields its place and goes". In the Tidal Model we believe it is important to remember that 'nothing lasts'. Heraclitus also was aware of the impermanence of the world, as well as our place within it. He said that "nothing is permanent but change" and, as a result, "we cannot step in the same river twice"

However, people can, and very often do, resist change, which often appears to bring many threats in its wake. As Andre Gide remarked: "Loyalty to the past stops us seeing that tomorrow's joy will come only if today makes way for it".

Because we recognise that change itself is never permanent we believe it is important to ask people about their experience of change. How do people change? What is happening within them, around them, and especially in their relationships with the world of others?

Since change is the only constant we must continually ask the person "what needs to be done now?" "What should we do next?"